Creating A Cleantech Jobs Engine

Published: October 11, 2017

A prescription for state governors to spur cleantech customer adoption -- moving promising startups from incubator spaces to factory floors, thus creating new jobs

A PROMISING LAUNCH OF CLEANTECH BUSINESS IDEAS

In 2005, I created and co-founded the Ignite Clean Energy Business Plan Competition (ICE) for the MIT Enterprise Forum of Cambridge to solve a recurring venture investor complaint. Startup presentations for funding requests were unintelligible. I heard statements like “Do you know what they are selling?” or “They may have great technology, but I do not get it.” or “It looks like a science experiment, not a business.” Scientists and investors did not speak the same language – scientists were fascinated by technology features, and venture capitalists wanted to know who was going to buy the new gadget, and why.

The ICE competition solved the communication problem. We required scientists to join teams that included business people so that an MIT inventor, for instance, had to form a team with an MBA student from Harvard University, Babson College, Boston University, or another business program. We recruited experienced business leaders and venture capitalists to mentor the teams utilizing a business plan “pitch” guideline we created.

In our first year of running the competition, 40 startup companies competed in the first round of judging. We whittled the companies to 11 finalists – who competed for $125,000 in cash and office space prizes. The competition was a great success and continues today as the Cleantech Open/Northeast.

… BUT, A LONG JOURNEY TO NOWHERE

I thought all was well in the cleantech startup world, but two years ago, I was asked to judge business plans from cleantech startups who received Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants. To my shock and dismay, I was reviewing many of the same companies that competed in the early ICE competitions. After ten years, these companies had made no progress towards commercializing their inventions and getting customers to adopt their technologies. The “companies” were still science projects.

Clearly, transitioning from early venture funding to gaining customer adoption is the next major challenge to get cleantech startups creating significant job growth.

… CAUSING VENTURE CAPITAL TO WALK AWAY, STIFLING GROWTH

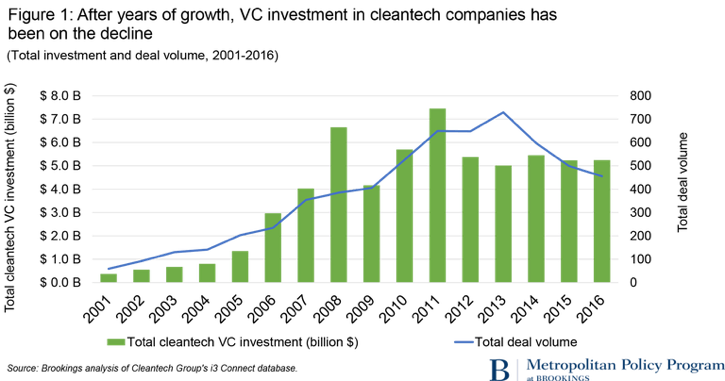

The lack of customers leads to a worse condition, venture capitalists who should be funding the early startups are looking to other industries for growth – abandoning cleantech and choking the innovation pipeline. VCs fund promising companies in high-growth industries, not struggling growth industries. The retreat of VCs interest is clear: “Between 2011 and 2016, VC cleantech investment declined by nearly 30 percent, from $7.5 billion to $5.24 billion.” [Cleantech venture capital: Continued declines and narrow geography limit prospects, published May 16, 2017 by Brookings]

A Solution: States Have Shown How To Spur Clean Energy Growth

State and city governments feel the brunt of climate change destruction from coastal hurricanes, western wildfires, droughts, or damaging winter coastal storms. To mitigate the causes of climate change, these local leaders have implemented policies to cut greenhouse gases through energy efficiency, renewable energy, and cap-and-trade programs. Their efforts have spurred job creation in the green-collar industries.

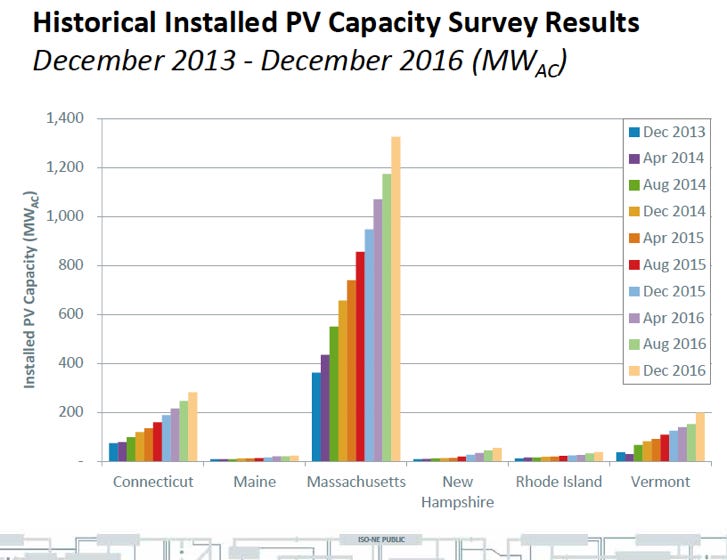

An example of state government policies that have driven renewable energy adoption in Massachusetts, especially when compared to the other New England states. In the region, Massachusetts has installed almost 70% of New England’s solar PV capacity, while Connecticut, Rhode Island, Maine, and New Hampshire only garnered 30% of the installations (source ISO-New England 2017 Final Solar PV Forecast).

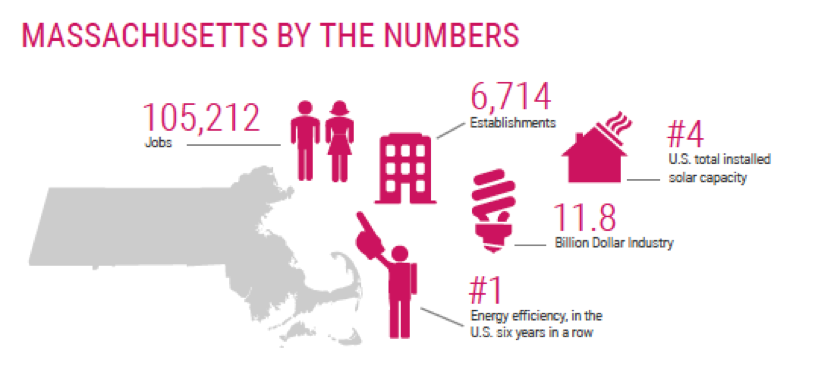

More importantly, as chronicled in the U.S. Climate Alliance Annual Report, the breadth of policies from state agencies, legislators, and governor Massachusetts has created the business environment for favorable clean energy growth. The result has been the creation of more than 105,000 clean energy industry jobs as of 2016 (source: 2016 Massachusetts Clean Energy Industry Report).

BUT, CLEANTECH BUSINESS GROWTH HAS NOT TAKEN OFF LIKE SOLAR

While Massachusetts, for instance, has been a leader in clean energy job growth, it has struggled to see the same increase in the riskier cleantech space.

Yes, the Bay State has a vibrant pipeline of exciting startups utilizing Greentown Labs, the largest maker-space cleantech startup hardware firms, the Massachusetts Technology Transfer Center for launching academic inventions, the Cleantech Open/Northeast for teaching entrepreneurs to make clear and compelling business plan pitches, MIT's The Engine for prototyping and product testing, and the InnovateMass program to provide grants for demonstration projects.

But, despite this highly successful engine to launch cleantech startups, Massachusetts still struggles to develop policies that move its many cleantech entrepreneurs from the lab to sustainable, profitable business enterprises with growing customers and revenues.

A POLICY PRESCRIPTION TO GROW CLEANTECH CUSTOMERS AND JOBS

Cleantech is different than in other industries. The inventions are not just software, which can spread to customers quickly but are often hardware devices that must connect to a complex electrical grid or building system. The electric grid, for instance, is not the open internet. It is a highly regulated and complex network that is not easily accessed.

Given industry complexity, new entrepreneurs of innovative cleantech devices struggle to find customers:

Who will risk trying the new devices;

Who can buy and connect them given the regulatory limits within states and utilities; and,

Who are easily reached for sales calls?

To overcome these barriers to customer adoption, state governors and legislators must take the lead by:

Becoming The First Reference Customer And Showing The Way Forward

All new businesses need at least one prime reference customer – an early adopter customer who will rave about the quality, service, and benefits received from the new company. But, who will take the first risk on the new startup innovator? It is a hard sell.

One idea: states and cities could set aside a small portion of their annual economic development budget to run an annual procurement competition to pick and install the most promising clean energy technologies into state/city buildings and spaces. Why? Most importantly, the state or city could assign their staff to provide feedback to the startup team on how well their prototype was performing.

In return for the opportunity to prototype their product or service with the state or city, the cleantech founders and investors would guarantee to continually improve the prototypes – fixing the inadequacies identified by the customer – until the product or service satisfies the early customers who will provide a positive and enthusiastic reference.

A well-documented example of an initial order that launched a company was the purchase of Big Belly, a solar-powered trash compactor. A case study of Big Belly shows that the firm got its start by its first sale: 500 solar-powered compactors and 210 recycling units to the city of Philadelphia, which replaced 700 wire trash cans. According to the case study, “the city collects only five times a week, at an annual operating cost of about $720,000-representing a 70 percent savings. The installation of solar compactors also enabled the Streets Department to deploy on-street recycling for the first time in Philadelphia.”

The initial sale to Philadelphia provided Big Belly a critical reference to sell to other cities. The city of Philadelphia became the critically needed reference to generate Big Belly’s sales to other cities. According to a Harvard Business School case study [9-816-005, October 26, 2015], “Bigbelly’s smart, connected waste and recycling bins were deployed in every U.S. state and 47 countries. The Needham, Massachusetts-based company with 52 employees had sold more than 30,000 units to 2,500 customers and counting.” A successful transition from an initial business idea to a sustainable business.”

Banding Together With Other States To Create A Single Marketplace

New businesses need large markets to entice investors and gain scale that drives production and distribution costs down. However, Cleantech firms, unlike computer technology firms, face small markets with fragmented state and utility regulations. Even with established technologies such as solar PV modules, market growth is highly dependent on state and utility rules.

But, there is an alternative to fragmented, small markets. Create a single cleantech and clean energy market across many states.

One example of a successful single market is the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), which was created by the northeastern states to reduce CO2 emissions from electricity generation plants. RGGI collaboration has been highly beneficial for the participating states. For example, through 2014, RGGI’s cap and trade system has created $1.37 billion payments back to the participating states. These funds have been used for investments and jobs in energy efficiency, clean and renewable energy, greenhouse gas abatement, and customer direct bill assistance. In addition, “the RGGI states have experienced a reduction of more than 45 percent in power sector CO2 pollution since 2005, even as the regional economy has grown 8 percent” (source: The Investment of RGGI Proceed Through 2014).

In addition to the RGGI framework of collaboration, three New England states – Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island – joined together for the Tri-State Clean Energy RFP. The purpose of the RFP was to solicit new utility-scale, wholesale power supplies. Eleven 20 MW to 126 MW wind and solar projects were selected from projects proposed in Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.

On a national basis, states’ governors also now have a new organization to create a unified market, the U.S. Climate Alliance, an organization of 15 states that launched after President Trump announced his intention to withdraw from the Paris Climate Accords. The Alliance is “committed to the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement” and plans “smart, coordinated state action [to] ensure that the United States continues to contribute to the global effort to address climate change”. The Alliance is well suited for creating a framework for a single cleantech and clean energy market within its participating states. The Alliance comprises more than 36% of the U.S. population and $7 trillion of U.S. GDP – a significantly large market [source: Alliance website]

How will a single cleantech and clean energy market work? Such a market will:

Standardize utility regulations and incentives across the participating states;

Standardize Renewable Portfolio Standard goals; and,

Coordinate permitting, taxing, and siting regulations.

Creating State-Supported Trade Missions To Expand Business Reach

Complex new equipment sales require one-on-one meetings and demonstrations. Selling online works great for commodities and established brands, but is not suitable for complex sales to corporate, municipal, university, or hospital customers.

Large prospective customer organizations have multiple levels of decision-makers and advisors. Senior sales executives logging expensive airplane travel, hotel rooms, and dinners must meet with these prospective customers. An optimistic sales cycle for the new product/service is nine months, but a practical sales cycle might be closer to 18 to 24 months as the new vendor must educate the prospective customer on why the firm should change from its current processes to a new practice. Plus, the new vendor must overcome customer resistance to try new technologies.

One model solution is to implement trade missions. Foreign countries use trade missions to cost-effectively market their country’s technology companies. An example is Swissnex, which features events to showcase Swiss technology companies.

Governors and mayors could work collaboratively with other states and cities to host cleantech fairs in each of their regions and invite prospective corporate customers to attend. For example, Wells Fargo Innovation Incubator looks for cleantech firms that can pilot their ideas in Wells Fargo buildings. A trade mission could open doors for high-level meetings with corporate executive decision-makers, such as Wells Fargo.

The Big Goal: New Jobs, Sustainable Growth, And Climate Protection

The ultimate goal is to grow new, sustainable businesses, with well-paying jobs, that also meet the needs of citizens in cities and states to reduce their carbon footprint. Increasingly, cities and states are looking for new ideas to address climate change and meet the Paris Accords despite the federal government’s abandonment of our global leadership position.